The Rise of the Studio System in 1930s Hollywood

Imagine you're in the 1930s, witnessing the rise of the studio system in Hollywood, where giants like MGM and Warner Bros. start to control every aspect of filmmaking. These studios not only produce and distribute films but also own the theaters where they're shown. This vertical integration gives them unparalleled power over the industry, even during the economic strains of the Great Depression. It's fascinating how this period shaped modern cinema, from the cultivation of star power to the enforcement of content regulations. But what exactly made this system so effective? Let's delve deeper.

Hollywood's Pre-War Transition

Hollywood's pre-war transition was characterized by rapid changes and innovations that fundamentally transformed the film industry. The late 1920s marked the adoption of sound technology, revolutionizing Hollywood and spurring a surge in film production. This era also witnessed the establishment of the studio system, with major studios seeking to leverage this new medium. By 1930, eight studios dominated 95% of American film production, with the Big Five—MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., 20th Century-Fox, and RKO—controlling most of the market.

During the Great Depression, cinema attendance soared, with an average of 80 million Americans attending movies weekly. Films provided an affordable escape from the harsh realities of daily life. This period also saw the implementation of the Production Code in 1934, which imposed strict moral guidelines on film content, shaping the narratives and themes prevalent in Hollywood films during the 1930s.

Major studios invested heavily in marketing and promotion, with MGM producing 16-18 films simultaneously at its peak. The efficiency of the studio system allowed studios to meet audience demand effectively, ensuring a steady stream of American films that captivated audiences throughout the decade.

Vertical Integration Strategies

In the 1930s, vertical integration strategies revolutionized Hollywood, with major studios managing every stage of film production, distribution, and exhibition. The Big Five studios owned around 2,600 initial-run theaters, granting them significant market control. They employed block booking, compelling independent theaters to accept bundled films, which ensured even lesser-known titles reached audiences and generated revenue.

Studio Ownership Structure

In the 1930s, Hollywood's studio ownership structure was transformed by vertical integration strategies, consolidating economic control within the industry. The Big Five studios—MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO—dominated the filmmaking process by controlling production, distribution, and exhibition. This strategy ensured their films reached audiences nationwide, establishing a near-monopoly by 1930, with eight studios overseeing 95% of American film production.

The Big Five owned around 2,600 initial-run theaters, which, while only 16% of the national total, generated three-fourths of the industry's revenue. This ownership allowed them to control film showings and schedules, bolstering their economic power. Their total assets were four times larger than those of the three minor studios, reinforcing their supremacy. This financial strength enabled the production of high-quality films and extensive marketing campaigns.

Vertical integration also provided a stable production environment. Long-term contracts with actors, directors, and other personnel ensured a steady output of films to cater to varied audience tastes. This approach not only boosted profits but also reinforced the Big Five's dominance in Hollywood.

Production Control Mechanisms

Major studios such as MGM, Paramount, and Warner Bros. maintained tight control over the filmmaking process through vertical integration. By owning production companies, theaters, and distribution networks, these studios dominated Hollywood's film industry, controlling 95% of American film output. This vertical integration allowed them to manage everything from casting to final edits, ensuring a consistent production environment.

Actors, directors, and crew members were often signed to long-term contracts, creating stability and predictability. This enabled studios to efficiently produce films that adhered to predefined genres and styles.

A key tactic in maintaining control was block booking, which forced theaters to purchase film packages that included both blockbuster hits and lesser-known titles. This strategy ensured that the entire slate of films reached audiences.

The studios' ownership of approximately 2,600 initial-run theaters, which generated three-fourths of the industry's revenue, further solidified their dominance. By controlling these theaters, studios could prioritize their films, maximizing profits and maintaining their grip on Hollywood's golden era.

Distribution and Exhibition

By leveraging vertical integration strategies, major studios did not just produce films; they controlled the entire process from script to screen. The Big Five—Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO—dominated American film production, controlling 95% of the market by 1930. Owning approximately 2,600 initial-run theaters, these studios ensured their films reached wide audiences, accounting for three-quarters of the industry's revenue.

Vertical integration empowered studios to dictate the terms of film exhibition. They invested heavily in their own theater chains, enabling exclusive screenings and maximizing profitability. One key tactic was block booking, which required independent theaters to purchase less desirable films along with popular titles. This practice further consolidated the Big Five's control over distribution and exhibition.

The economic success of the Hollywood studio system also depended on global distribution. By 1925, foreign rentals represented half of the American feature revenues, highlighting the importance of international markets. Through these strategies, the Big Five orchestrated the entire lifecycle of their films—from production and distribution to exhibition—ensuring a steady stream of revenue and cementing their dominance in the industry.

Dominance of the Big Five

In 1930s Hollywood, five powerhouse studios—MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO—weren't just industry leaders; they practically owned it. These Big Five dominated the studio system, controlling about 95% of American film production by 1930, setting the stage for the Golden Age of Hollywood.

MGM, the largest studio, emphasized middle-class values and managed a massive star system that included iconic figures like Clark Gable and Judy Garland. Their film production focused on creating high-quality, widely appealing movies, cementing their place in Hollywood history.

Paramount Pictures gained attention for its sophisticated productions. Known for adapting Broadway hits into successful films, Paramount played a key role in elevating the overall quality of Hollywood's offerings. Warner Bros., on the other hand, produced cost-efficient films aimed at working-class audiences, achieving notable success with *The Jazz Singer*, the first sound feature film released in 1927.

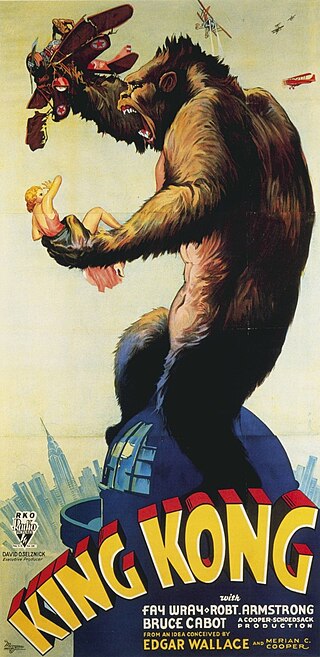

RKO, though the smallest of the Big Five, left an indelible mark with critically acclaimed films like *Citizen Kane* and *King Kong*. Their diverse offerings contributed greatly to the period's iconic films, showcasing the breadth and depth of Hollywood's studio system.

Role of Minor Studios

Minor studios played an essential role in the 1930s Hollywood landscape. By producing low-budget B movies, studios like Republic and Monogram served as training grounds for future stars and provided second features in double bills. These films met the demand for affordable entertainment and enriched the industry's diversity.

Low-Budget Film Production

During the 1930s, minor studios like Republic, Monogram, and Grand National found their place in Hollywood by focusing on low-budget film production. These studios specialized in B movies, churning out 40-50 films annually to serve as second features alongside major studio releases. Operating with limited financial resources, they targeted niche audiences, ensuring a steady output that significantly contributed to the film economy during the Great Depression.

Despite budget constraints, these studios succeeded by tapping into popular genres such as Westerns and horror films, which quickly gained traction with American audiences. This model allowed minor studios to maintain a consistent marketplace presence, offering a variety of entertainment options at lower costs.

Rising stars like John Wayne often appeared in these low-budget films, gaining valuable experience that facilitated their transition to major studio productions later on. The B movie production model not only kept minor studios afloat during tough economic times but also played a crucial role in shaping American cinema by fostering creativity and innovation within limited budgets.

Training Ground for Stars

Minor studios like Republic, Monogram, and Grand National, though often overshadowed by their major studio counterparts, played a crucial role in Hollywood by nurturing future stars. These studios specialized in low-budget B movies, providing essential early acting opportunities for aspiring actors. John Wayne, for instance, honed his craft in these high-volume production environments, developing the skills needed to become a major star.

Producing around 40-50 films annually, these minor studios contributed a steady stream of content that complemented the major studios' A-list features. This prolific output allowed actors to gain visibility and build their careers in the competitive Hollywood landscape. Moreover, the low-budget model enabled a diverse range of genres and storytelling styles, enriching the film industry during the 1930s.

At a time when major studios focused on high-budget productions, B movies from minor studios offered accessible entertainment options, especially significant during the Great Depression. This reinforced cinema's role as a popular cultural medium. Hence, these minor studios were instrumental in training and launching Hollywood's future stars.

Second Features in Double Bills

Minor studios not only served as training grounds for budding stars but also played a crucial role in the double bill format that characterized 1930s and 1940s cinema. Studios like Republic, Monogram, and Grand National produced low-budget B movies, ensuring a consistent supply of second features. These films accompanied A-list movies, providing working-class audiences with more value for their ticket price, especially during the Great Depression.

Producing around 40 to 50 films annually, these minor studios operated on tight budgets yet managed to train future stars like John Wayne. Their genre films, including Westerns and horror, filled niches that major studios like MGM and Paramount often overlooked. This collaboration between major and minor studios highlighted an economic strategy designed to optimize revenue and ensure profitability. By pairing established hits with lesser-known B movies, major studios maintained high audience attendance, benefiting both parties.

Double bills offered an immersive cinematic experience that captivated audiences, making the combination of major and minor studio productions essential to the era's film industry. The minor studios' ability to produce engaging second features was key to sustaining the popularity of double bills.

Economic Control and Impact

In the 1930s, Hollywood's studio system solidified its economic dominance over the film industry, evolving into a juggernaut of production and profitability. The Big Five—MGM, Paramount, Warner Bros., Twentieth Century-Fox, and RKO—exercised control through vertical integration, overseeing production, distribution, and exhibition. These studios owned approximately 2,600 initial-run theaters, generating about 75% of the industry's revenue, ensuring their financial success.

MGM stood out as the most financially successful studio of the decade, producing up to 18 films simultaneously. In contrast, RKO struggled with profitability. The economic impact of these studios was profound, with the film industry surpassing office machinery in financial size and offering a vital morale boost during the Great Depression. Around 80 million Americans attended movies weekly, making Hollywood a central aspect of American life.

The introduction of the Production Code in 1934, which aimed to meet audience expectations for moral standards, ensured widespread acceptance and economic stability. This strategic move helped studios maintain their market grip, reinforcing their dominance and financial success. In summary, the Hollywood studio system of the 1930s wielded unparalleled economic power, shaping the film industry's landscape.

Production Code Enforcement

Following the economic dominance established by the studio system, Hollywood faced a new challenge: ensuring films adhered to moral standards amidst a rapidly changing social landscape. In 1934, the Production Code established strict guidelines prohibiting depictions of passion, adultery, and illicit sex unless essential to the plot, greatly shaping Hollywood's Golden Era film narratives. As a result, film studios had to navigate these regulations carefully.

Scripts required approval before filming and completed films needed a Production Code Seal for distribution. This streamlined the production process and ensured that each film adhered to moral standards. Noncompliance could result in fines of up to $25,000, incentivizing studios to rigorously follow these guidelines to avoid economic repercussions.

During the Great Depression, enforcing the Production Code was vital as studios aimed to align their films with public opinion and moral expectations, ensuring box office success. While these regulations standardized storytelling, they also restricted artistic expression until the Code's decline in the 1960s. The enforcement of the Production Code played an important role in shaping Hollywood films, balancing economic interests with societal values.

Innovations by Key Directors

Innovations by key directors in 1930s Hollywood revolutionized the film industry, captivating audiences with novel narrative styles and pioneering techniques. Frank Capra and John Ford emphasized relatable characters and social issues, crafting films that deeply resonated during the Great Depression. Their inventive storytelling turned cinema into a mirror of the times, captivating audiences with narratives they could personally connect with.

Alfred Hitchcock's mastery of suspense and psychological thrillers set him apart. His innovative use of camera angles and editing in films like "Psycho" heightened tension, keeping viewers on the edge of their seats. This imaginative approach to psychological storytelling redefined audience engagement.

Orson Welles' "Citizen Kane," though released in 1941, epitomized the culmination of 1930s innovations. Utilizing deep-focus photography and non-linear storytelling, Welles transformed cinematic techniques, making "Citizen Kane" a landmark in film history.

Howard Hawks excelled in comedy, pioneering the screwball genre with "Bringing Up Baby." His rapid-fire dialogue and intricate character dynamics established a new template for comedic narrative in cinema.

Advances in sound technology also played a pivotal role. Directors like Welles incorporated radio techniques to enhance emotional depth and narrative clarity, marking a significant evolution in how films utilized audio.

These directors' innovations collectively transformed the artistic and technical landscape of Hollywood, setting enduring standards for future filmmakers.

Influence on Modern Filmmaking

Modern filmmaking continues to thrive on principles established during 1930s Hollywood, particularly those of the studio system. This system's vertical integration model, where studios controlled production, distribution, and exhibition, still influences today's major studios. Such control ensures that films reach a wide audience, securing financial success and market dominance.

The star system, where actors were groomed and marketed to fit specific personas, remains a significant strategy. Studios continue to cast and promote actors based on their marketability, impacting both casting decisions and promotional campaigns.

Technical innovations in sound recording, color, and special effects, first developed during the studio era, set the standards for current film production. Although these advancements have evolved, they remain rooted in the practices of Hollywood's Golden Era.

Genre specialization established during the studio period laid the groundwork for today's blockbuster filmmaking. Studios focus on franchises and predictable narratives to captivate audiences and guarantee box office success.

Lastly, the influence of the Hays Code on content guidelines has evolved into modern rating systems. These guidelines continue to shape the content and storytelling of contemporary films, showcasing the lasting impact of the studio system on modern filmmaking practices.