What Are Some Famous Technicolor Films?

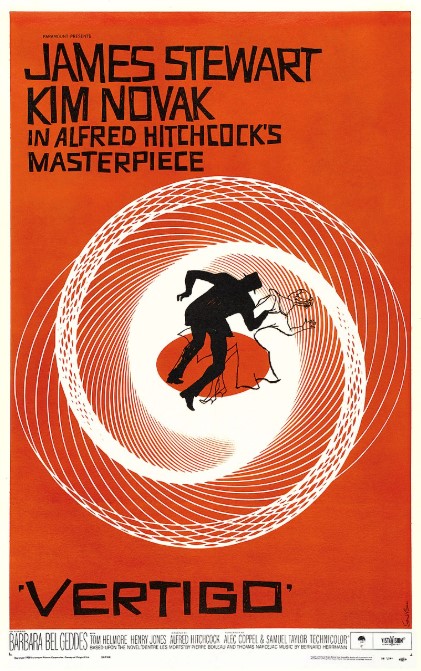

Technicolor films revolutionized cinema with their vibrant palette, including early breakthroughs like "Becky Sharp" (1935) and timeless classics like "The Wizard of Oz." You'll recognize Hitchcock's psychological masterpiece "Vertigo," Disney animations such as "Bambi," and dazzling musicals like "Singin' in the Rain." Adventure films including "The Adventures of Robin Hood" showcased exotic landscapes in stunning color.

The technique transformed storytelling across genres, creating unforgettable visual experiences that continue to captivate audiences today.

Key Takeaways

- "The Wizard of Oz" (1939) stands as one of the most iconic Technicolor films, famously transitioning from sepia to vibrant color.

- "Gone with the Wind" (1939) showcased Technicolor's ability to capture epic historical drama with rich, saturated hues.

- "Singin' in the Rain" (1952) represents a quintessential Technicolor musical featuring vibrant costumes and spectacular dance sequences.

- "The Adventures of Robin Hood" (1938) utilized Technicolor to highlight Sherwood Forest's verdant landscapes and Errol Flynn's scarlet tunics.

- "Vertigo" (1958) demonstrated Hitchcock's masterful psychological use of Technicolor to create dreamlike, unsettling atmospheres.

Technicolor’s Transformative Role in Film History

The revolutionary Technicolor process transformed cinema by introducing vibrant, saturated colors that captivated audiences and created visual spectacles unlike anything seen before.

When exploring famous Technicolor films, you'll discover iconic works like The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), where Errol Flynn's swashbuckling adventures shine in dazzling color. The Wizard of Oz (1939) masterfully uses the process to contrast Kansas's sepia tones with Oz's vibrant palette.

Black Narcissus (1947) demonstrates how Technicolor's lush saturation can enhance psychological storytelling in its depiction of nuns in the Himalayas. An American in Paris (1951) showcases the technique's artistic potential through its legendary 17-minute ballet.

Finally, Hitchcock's Vertigo (1958) employs Technicolor's dreamlike qualities to intensify the film's psychological suspense, proving the process's versatility beyond mere spectacle.

The 1940s represented a golden era for Technicolor with productions like The Gang's All Here (1943) demonstrating how three-strip process enabled filmmakers to create more dynamic and visually striking cinematic experiences.

The Golden Age of Technicolor: 1930s Breakthrough Films

While famous Technicolor films span decades of cinematic history, the groundbreaking innovations of the 1930s established the foundation for color filmmaking's future. When Becky Sharp debuted in 1935, it marked the first full-length feature using the three-strip Technicolor process.

That same year, musicals embraced the vibrant technology with Gypsy Sweetheart and Show Kids, while The Little Colonel incorporated colored sequences alongside traditional cinematography.

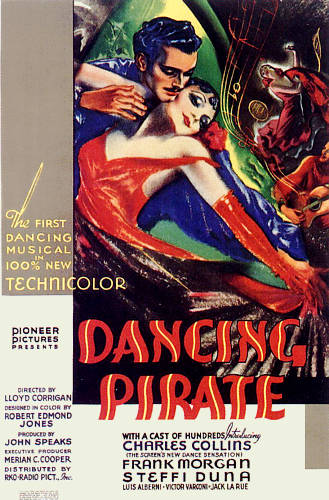

The Mitchell Camera became essential for capturing "Color by Technicolor" productions, as showcased in 1936's Dancing Pirate. By 1938, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer demonstrated how talented cinematographers like James Wong Howe could elevate the medium.

These early Technicolor movies laid groundwork that would later be perfected by cinematographer Jack Cardiff and designer Alfred Junge in Powell and Emeric Pressburger's renowned productions.

The most iconic examples of Technicolor's emotional impact came with 1939's The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind, which utilized vibrant color palettes to amplify narrative elements and character development.

Magical Worlds: Fantasy and Animation in Technicolor

Vibrant colors transformed fantasy and animation into truly magical experiences once Technicolor's three-strip process became available to filmmakers. Unlike early black-and-white films, Disney masterpieces like Bambi and The Adventures of Ichabod showcased what critics called "Glorious Technicolor," bringing animated worlds to life with unprecedented richness.

The three-strip camera captured the whimsical storybook quality of Alice in Wonderland (1951), while The Blue Bird (1940) used color filters and matte paintings to enhance its fantastical elements—much like the Emerald City dazzled audiences in earlier color productions. Cinderella (1950) wasn't the first feature to use this technology, but its enchanting atmosphere demonstrated how Technicolor could elevate romantic storytelling.

Similarly, The Adventures of Robin Hood proved that vibrant hues could intensify action sequences just as effectively as magical domains. Disney's pioneering film Flowers and Trees (1932) revolutionized the animation industry by being one of the first to fully embrace Technicolor, establishing new visual standards that captivated global audiences.

Hitchcock's Color Palette: Psychological Thrillers in Technicolor

Master of suspense Alfred Hitchcock transformed psychological thrillers by wielding Technicolor as a powerful emotional tool rather than mere decoration. In his landmark film Vertigo (1958), he collaborated with cinematographer Robert Burks to create dreamlike atmospheres where color reflected the protagonist's fractured psyche.

Hitchcock deliberately used red, yellow, and green as "traffic light indicators" of characters' psychological states. The film featured innovative visual techniques, including a spiraling nightmare sequence designed by Abstract Expressionist John Ferren.

This color-psychology approach wasn't unique to Hitchcock. Niagara (1953) employed Technicolor's saturated reds to heighten tension when Monroe's character is silhouetted in darkness. Similarly, Black Narcissus (1947) used Technicolor's lush palette to convey the psychological unraveling of Himalayan nuns amid exotic surroundings.

While Hitchcock often used color brilliantly, his choice to film Psycho in black and white intensified the shower scene impact by focusing viewers on psychological terror rather than graphic violence.

Singing in Color: Landmark Technicolor Musicals

Golden spotlights and swirling satin gowns transformed the silver screen as Technicolor revolutionized the movie musical. Unlike their black and white predecessors, these films dazzled audiences with vibrant spectacle.

You'll marvel at Gene Kelly's exuberant performance in "Singin' in the Rain" (1952), the quintessential Technicolor musical that Warner Bros. rivals couldn't match. The Adventures from monochrome to great Technicolor reached new heights in "An American in Paris" (1951), featuring a stunning 17-minute ballet sequence set against a colorful New York-inspired backdrop.

British Film entered this vibrant arena with "The Red Shoes" (1948), which used color negative film techniques to create its emotionally intense 15-minute ballet sequence, proving that Technicolor's first impact on musicals would forever change how you experience cinematic song and dance.

Exotic Landscapes: How Technicolor Transformed Adventure Films

Beyond the song-and-dance spectacles, Technicolor breathed life into far-flung worlds that audiences could only dream of visiting. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) showcased verdant forests where our hero battled Prince John, with the dye transfer process capturing every emerald leaf and scarlet tunic.

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's Black Narcissus (1947) used Technicolor's beam splitter technology to intensify the psychological drama unfolding in a Himalayan convent—a masterclass in color symbolism rivaling Hitchcock's later work with Scottie Ferguson.

Jean Renoir abandoned his black-and-white sensibilities for The River (1951), while Cobra Woman (1944) transported viewers to exotic South Seas islands through its two strips of vibrant imagery. Like The Wizard of Oz (1939), these films represented Life and Death through color's transformative power.