The Role of Women in 1930s Hollywood: On-Screen and Behind the Scenes

Explore how women in 1930s Hollywood navigated a landscape dominated by the patriarchal studio system and the stringent Production Code. Despite these barriers, actresses like Bette Davis and Jean Harlow managed to shine, portraying complex and memorable characters. Behind the scenes, female writers and directors faced steep challenges, with their numbers dwindling as studios reinforced traditional gender norms. What impact did this have on the films produced, and how did these dynamics shape the industry's evolution?

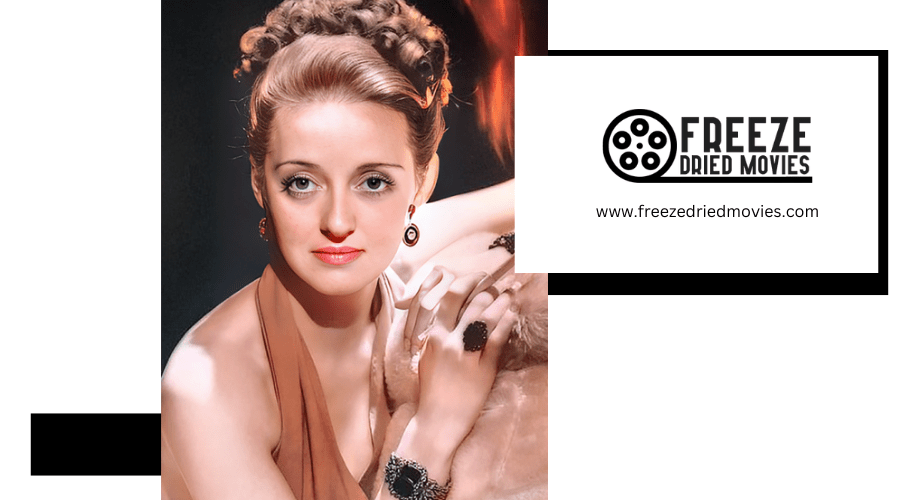

Key Actresses of the 1930s

Despite the challenges Hollywood faced in the 1930s, it celebrated the rise of several iconic actresses who left an indelible mark on the film industry. Bette Davis, Jean Harlow, and Anna May Wong emerged as significant figures, each forging their own path in a male-dominated industry.

Bette Davis is remembered for her intense performances in *Of Human Bondage* (1934) and *Jezebel* (1938). She was not only a phenomenal actress but also a pioneer who fought against the restrictive studio system, demanding creative control over her roles. Her determination set a precedent for women in Hollywood.

Jean Harlow, known as the "Blonde Bombshell," captivated audiences with her roles in *Dinner at Eight* (1933) and *Bombshell* (1933). She became one of the highest-paid actresses of her time, symbolizing the sexualized image of women prevalent in 1930s cinema. Her glamorous persona and bold characters left a lasting impression.

Anna May Wong, the first Chinese-American movie star, overcame significant racial barriers to make notable contributions with roles in films like *Shanghai Express* (1932). Despite the limited and often stereotypical roles available to her, Wong's work highlighted the challenges of Asian representation in Hollywood, paving the way for future generations.

Production Code and Censorship

Even as iconic actresses like Bette Davis, Jean Harlow, and Anna May Wong were making their mark, Hollywood's creative freedom faced significant constraints. The Production Code, enforced in July 1934, imposed strict limitations on film content, profoundly impacting the representation of women and reinforcing traditional gender roles. The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) mandated that films receive approval from the Production Code Administration (PCA), restricting narrative complexity and women's agency in films.

Female characters often shifted towards submissive roles, with a focus on their bodies rather than their stories. This censorship promoted conservative values and formulaic storytelling, sidelining women's voices. The PCA's restrictions on the representation of women made it challenging to portray strong, complex female characters.

Three significant impacts of the Production Code were:

- Reinforcement of Traditional Gender Roles: Female characters were often depicted in submissive, domestic roles.

- Reduction in Narrative Complexity: Stories with complex, independent women were rare due to censorship.

- Limitation on Women's Agency: Films could not show women as having significant control over their lives and decisions.

The legacy of the Production Code lingered until its revocation in 1968, continuing to influence Hollywood's portrayal of women.

Racial Representation and Challenges

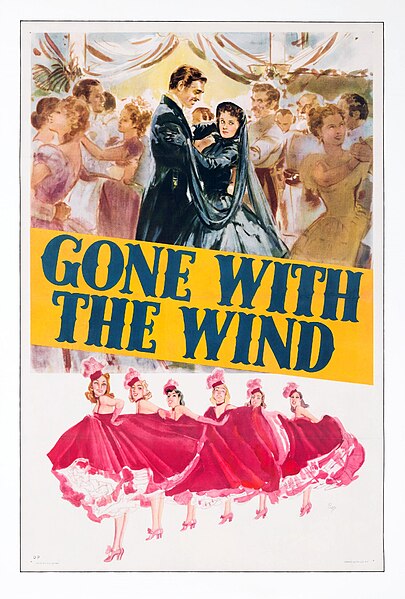

Racial representation in 1930s Hollywood posed significant challenges for actresses of color, who faced systemic barriers and stereotyping. Actresses like Anna May Wong were often relegated to stereotypical roles and missed out on major opportunities. For instance, Wong was denied the lead role in *The Good Earth* (1937) due to miscegenation laws. Similarly, Lupe Vélez was frequently cast in roles that reinforced the "feisty Latina" stereotype, while African American actresses like Hattie McDaniel were often limited to roles such as the mammy, exemplified by her performance in *Gone With The Wind* (1939).

The institutionalized oppression in Hollywood marginalized women of color, significantly reducing their presence in prominent roles. By the 1940s, actresses of color comprised only about 14% of female characters in films. The 1934 Production Code further restricted their portrayal, enforcing conservative values that often neglected their complexity and individuality. These dynamics reflected societal biases and perpetuated harmful stereotypes, severely limiting storytelling opportunities for women of color.

Thus, the racial representation of female characters in 1930s Hollywood was both limited and fraught with challenges, underscoring the systemic inequalities that actresses of color had to navigate to find meaningful work in the industry.

Studio System and Star Power

How did the studio system shape the careers of women in 1930s Hollywood? The studio system, which dominated the film industry, controlled every aspect of production, distribution, and exhibition, significantly impacting roles for women both on and off the screen. Opportunities for women drastically declined, with their presence in film castings dropping from 40% in the 1910s to just 20% by 1930.

The system's preference for male directors and producers left scant opportunities for women in these roles. Female stars like Bette Davis and Jean Harlow had to navigate complex studio politics to assert their influence. Davis's battles against studio control highlight the difficulties women faced in gaining autonomy.

Moreover, the enforcement of the Production Code in 1934 imposed strict moral guidelines, often relegating women to traditional roles and limiting their agency, further constraining female representation and influence during Hollywood's Golden Era.

Key Impacts on Women:

- Limited Roles: Women were often cast in traditional, less dynamic roles.

- Reduced Opportunities: There was minimal female involvement in directing or producing.

- Scapegoating: Female stars were often unfairly blamed for box office failures during economic downturns, as seen in the 1938 Hollywood crisis.

Thus, the studio system heavily restricted women's contributions in 1930s Hollywood.

Legal Battles and Industry Changes

The studio system's dominance in Hollywood began to weaken due to legal battles and industry changes, reshaping opportunities for women in film. A pivotal moment was Olivia de Havilland's 1943 lawsuit against Warner Bros., which culminated in the De Havilland Law of 1945. This law limited studios from arbitrarily extending actors' contracts, thereby shifting power dynamics and granting actors, including women, greater control over their careers.

In 1948, the antitrust case against Paramount Pictures further eroded the major studios' monopolistic grip on film production and distribution. This decision paved the way for independent filmmakers, fostering more diverse and innovative storytelling. Women directors, previously constrained by the studio system, began to find opportunities to share their unique perspectives.

The decline of the stringent Production Code, which had restricted women's representation in multifaceted roles, also contributed to this transformation. As Hollywood evolved, these legal battles and industry changes cultivated a more inclusive environment. Independent filmmaking thrived, empowering female filmmakers to emerge and craft new narratives. These developments signaled the dawn of a new era in Hollywood, where women could reclaim creative control and shape the industry's future.

Gender Representation Trends

From the 1910s to the 1930s, female roles declined sharply from 40% to 20%. This trend reflects a male-dominated studio system that marginalized women's participation. Legal changes, such as the Hays Code, further limited complex female characters, reinforcing traditional gender norms.

Decline in Female Roles

During the 1930s, Hollywood experienced a significant decline in female roles, reflecting broader trends that marginalized women in the film industry. Female representation in film roles fell sharply from 40% in the 1910-1920 period to just 20% by 1930. This decline coincided with the rise of the studio system, which often relegated women to traditional gender roles and limited their opportunities for complex portrayals.

The introduction of the Production Code in 1934 further restricted these opportunities, reinforcing the industry's preference for traditional gender roles. The U-shaped pattern of gender representation illustrates a steep drop in female roles post-1920, with a gradual recovery only after 1950. By the 1930s, women had nearly vanished from directing and producing roles, reflecting a male-dominated studio system that favored male directors and writers.

Key points to consider:

- Decline in Female Roles: Female representation dropped markedly by the 1930s.

- Studio System Impact: The studio system solidified male dominance in directing and producing roles.

- Traditional Gender Roles: The Production Code reinforced traditional gender roles, limiting complex female roles.

Understanding this decline provides crucial context for Hollywood's gender dynamics.

Impact of Studio System

The rise of the studio system in Hollywood between 1915 and 1920 fundamentally reshaped gender representation trends, significantly sidelining women both in front of and behind the camera. This transition from independent filmmakers to dominant studios created structural barriers that sharply diminished women's roles. By 1930, female participation in film roles had plummeted to 20%, a stark contrast to the 40% during the silent film era of the 1910s.

The male-dominated studio system nearly eradicated opportunities for women in directing and producing, skewing representation trends in favor of men. The enforcement of the Production Code in 1934 further exacerbated this issue by prioritizing conservative values that marginalized complex female characters.

A quick look at this period:

| Period | Female Participation | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1910s | 40% | Numerous opportunities, diverse roles |

| 1920s | Decline begins | Rise of studio system, fewer roles |

| 1930 | 20% | Structural barriers, male-dominated roles |

| Post-1934 | Further decline | Production Code, conservative values |

This table highlights how the studio system reduced women's presence in American film, eroding their representation across all job types.

Legal Changes Influence

In the male-dominated studio system of Hollywood, significant legal changes began to reshape gender representation trends. Olivia de Havilland's 1943 lawsuit against Warner Bros. led to the establishment of the De Havilland Law, which limited studios' ability to extend actors' contracts indefinitely. This pivotal legal change provided actors, including women, with more freedom and opportunities in Hollywood.

The 1948 antitrust case against Paramount Pictures further dismantled the studio system's exclusive control, allowing for more competition and increased participation of women in various filmmaking roles, including directing and producing. These legal victories fundamentally altered power dynamics, enabling women to break into previously male-dominated areas.

In the wake of these changes, studies revealed that as industry power became less concentrated, the number of women producers increased, fostering greater gender diversity in film projects. Here are three key outcomes:

- Increased Opportunities: The De Havilland Law allowed female actors to pursue diverse roles.

- Expanded Roles: More women began to take on directing and producing positions.

- Greater Representation: Legal changes led to a gradual improvement in gender diversity across Hollywood.

Despite these advances, systemic barriers to equal representation remain, highlighting the ongoing struggle for gender equality in the industry.

Cultural and Economic Impacts

As you investigate the cultural and economic impacts on women in 1930s Hollywood, you'll see how the Production Code confined female characters to traditional roles, limiting their complexity. Economic pressures from the Great Depression exacerbated the precariousness of actresses' careers, with stars like Joan Crawford often unfairly blamed for box office failures. The studio system's male-dominated hierarchy further restricted women's opportunities behind the camera, reinforcing gender roles both onscreen and off.

Economic Pressures on Actresses

Economic pressures on actresses in 1930s Hollywood were immense, driven by both cultural and financial forces. The rigid studio system commodified actresses' personas, often leading to economic exploitation. Despite their popularity, actresses faced significant financial disparities. For instance, the highest-paid actresses in 2013 earned $181 million, starkly contrasted by the $465 million earned by male counterparts, highlighting ongoing inequalities rooted in this era.

Several factors compounded these pressures:

- Production Code: Enforced in 1934, it limited the themes and complexity of female characters, reducing actresses' economic opportunities within the studio system.

- 1938 Crisis: Independent theater owners blamed actresses like Joan Crawford for box office failures, illustrating how economic pressures unfairly targeted female stars.

- Legal Battles: Cases like Olivia de Havilland's lawsuit against Warner Bros. in 1943 eventually shifted power dynamics, enhancing actresses' negotiating power and economic opportunities.

The rise of television further exacerbated these pressures by contributing to the film industry's downturn. However, these legal battles slowly began to provide actresses with a stronger foothold in Hollywood, setting the stage for more equitable treatment in subsequent decades.

Studio System's Gender Roles

The immense economic pressures on actresses in 1930s Hollywood were compounded by the rigid gender roles enforced by the studio system. Female representation plummeted, with women actors making up only 20% of film casts by 1930, a steep decline from 40% in the previous decade. The Hays Code strictly enforced traditional portrayals, relegating women to love interests or secondary characters without agency.

| Aspect | Impact on Women |

|---|---|

| Female Representation | Decreased to 20% by 1930 |

| Creative Roles | Nearly zero opportunities |

| Traditional Portrayals | Limited to secondary roles |

| Legal Changes | Long-term opportunities |

The Production Code's conservative values favored male perspectives, reducing the complexity of female characters. This resulted in films that often marginalized women's experiences and contributions. Behind the scenes, the studio system excluded women from key creative roles such as directing and producing. By 1930, opportunities for women in these positions were nearly non-existent, as studios preferred hiring male directors and writers.

Legal changes, such as Olivia de Havilland's lawsuit against Warner Brothers, began to shift power dynamics, eventually leading to more opportunities for women in Hollywood. These changes, however, were slow and came only after decades of struggle against the entrenched gender roles of the studio system.

Production Code's Influence

Introduced in 1934, the Production Code drastically reshaped Hollywood's cultural and economic landscape by imposing strict guidelines that curtailed the depiction of women's roles. Films produced before the Code often showcased complex female characters, but post-Code films reduced women to traditional, submissive roles, reflecting the moral conservatism of the time.

The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) mandated that all films receive prior approval from the Production Code Administration (PCA). Without the PCA seal, films faced severe financial penalties, fundamentally altering Hollywood's storytelling and narratives, particularly impacting the portrayal of female characters.

Key Impacts of the Production Code:

- Restricted Women's Roles: Female characters were often depicted in limited, stereotypical roles, reinforcing gender stereotypes.

- Economic Constraints: Financial penalties for non-compliance led studios to prioritize conservative content over nuanced storytelling.

- Decline of Female Creatives: The emphasis on marketable, conservative values contributed to a decline in female film writers and directors.

The legacy of the Production Code persisted until its revocation in 1968, leaving a long-term impact on Hollywood's portrayal of women and reinforcing existing gender stereotypes within the film industry.