How Revisionist Westerns Challenged Traditional Tropes

You're watching an old Western when you notice something's off—the heroic cowboy isn't so heroic, the gunfight isn't gloriously choreographed, and the indigenous characters aren't one-dimensional villains. This isn't your grandfather's Western. Since the 1960s, revisionist Westerns have systematically dismantled the mythmaking of traditional frontier narratives, challenging what you thought you knew about America's past. These films don't just entertain; they force you to confront uncomfortable truths about violence, racism, and the complex moral landscape of the American frontier.

The Violent Reality: Deconstructing Glorified Gunfights

Blood splatters across the screen not as heroic punctuation but as horrifying consequence in revisionist Westerns. You're witnessing a deliberate deconstruction of the sanitized shootouts that traditional Westerns peddled for decades.

Films like "Unforgiven" expose gunfights as they truly would be: clumsy, terrifying affairs where moral clarity dissolves in the gunsmoke.

Sam Peckinpah's revolutionary filming techniques in "The Wild Bunch" force you to confront the shocking brutality behind Hollywood's previously glamorized violence. The Western genre's comfortable mythology crumbles as these films strip away romantic notions of frontier justice.

Unlike the films of the 1940s where John Ford's direction established clear standards for heroism and integrity, revisionist Westerns deliberately complicate these moral frameworks.

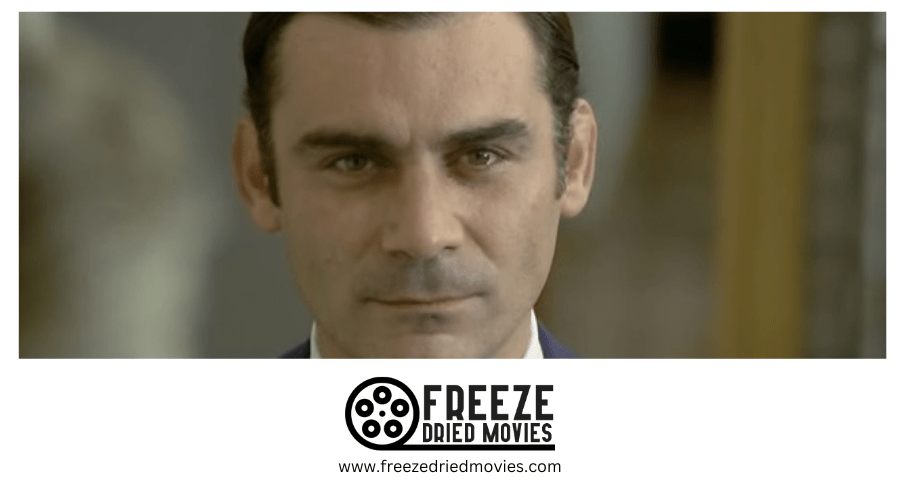

Even modern entries like "No Country for Old Men" continue this tradition, systematically denying you the moral triumph that traditional Westerns promised, leaving instead morally ambiguous landscapes where violence yields no heroes, only consequences.

Shifting Perspectives: Centering Marginalized Voices in the West

While traditional Westerns cast their heroes from a predictable mold—white men taming the "savage" frontier—revisionist Westerns deliberately fracture this narrow perspective. You'll find films like "Chato's Land" and "Little Big Man" transforming Native Americans from simplistic "bad guys" into complex characters with legitimate grievances against United States expansion.

The American Western evolved further by disrupting gender norms, as in "McCabe & Mrs. Miller," where female protagonists challenge the traditional Western hero archetype. Films like "Django Unchained" offer a new perspective by using the genre to confront America's racist history.

This revisionist approach shifts the viewpoint away from conquest narratives, instead centering voices previously silenced in frontier mythology. By amplifying marginalized experiences, these films reveal a more truthful, multifaceted portrayal of the West. These reimagined narratives contrasted sharply with the 1940s Western films that celebrated a pioneering spirit and reinforced a romanticized national identity rooted in frontier mythology.

Morally Gray Heroes: The End of the White Hat vs. Black Hat Binary

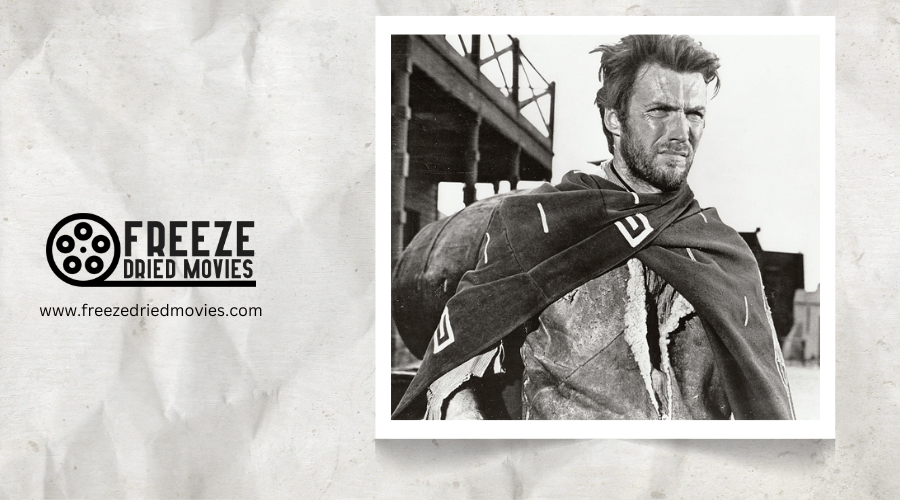

Traditional Westerns broke down as filmmakers tore apart the simplistic moral framework that had defined the genre for decades. You'll notice this shift in Revisionist Westerns, where protagonists occupy morally ambiguous territory rather than clear-cut heroism.

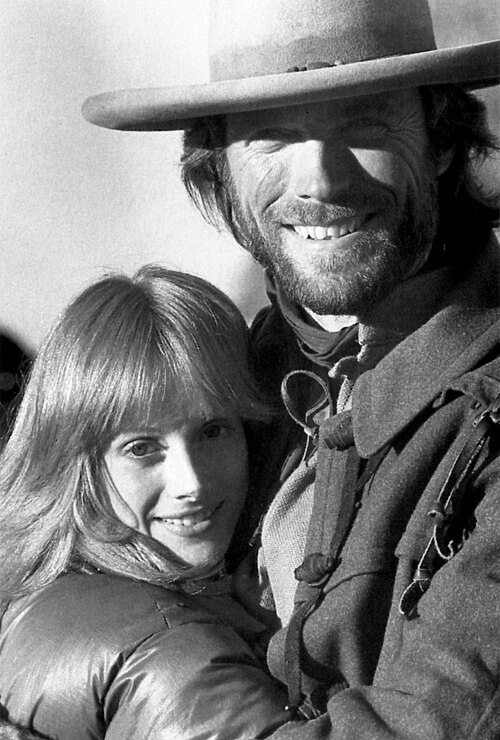

Consider Clint Eastwood's William Munny in *Unforgiven*, a reformed killer forced to confront his violent past, challenging the idealized hero archetype. Similarly, *The Wild Bunch* portrays aging outlaws as desperate men confronting their obsolescence rather than noble figures.

No Country for Old Men takes this moral complexity further by denying viewers the cathartic showdown between good and evil. Instead, Anton Chigurh moves through the landscape as an unstoppable force, forcing you to reconsider frontier mythology's simplistic morality. These films demand you grapple with the uncomfortable truth: justice in the West was rarely black and white.

This complexity stands in stark contrast to John Wayne's earlier characters who embodied rugged individualism and frontier justice without moral ambiguity.

Confronting Historical Truths: Slavery, Colonialism, and Indigenous Genocide

Beyond moral ambiguity, Revisionist Westerns confront the darkest chapters of American history that classic films deliberately ignored. You'll notice how Django Unchained places slavery at its narrative core, challenging the Traditional Western's erasure of Black experiences in the Old West.

The Proposition exposes British colonial brutality in Australia, depicting cyclical violence between settlers and indigenous peoples—a stark contrast to romanticized frontier narratives. Similarly, Dead Man and No Country for Old Men refuse to erase Native American perspectives, instead highlighting the genocidal consequences of westward expansion.

Films like Unforgiven and The Sisters Brothers subvert the genre's glorification of violence, while The Power of the Dog examines toxic masculinity's devastating impact on marginalized communities. These works force you to reckon with America's complex historical legacy rather than consuming comfortable myths.

Cultural Reflections: How Changing American Values Transformed the Western

As America's social consciousness transformed through the turbulent 1960s and 1970s, the Western genre underwent a profound metamorphosis that mirrored these shifting cultural values. You could see this evolution in Sam Peckinpah's "Wild Bunch," which depicted graphic violence reflecting Vietnam War disillusionment. The Western sub-genre of Spaghetti Westerns challenged the moral certainty once embodied by James Stewart's characters.

Clint Eastwood's morally ambiguous gunmen replaced traditional heroes as environmental concerns and counterculture movements rejected frontier mythology. Films like "Garrett and Billy" questioned authority figures during the post-Watergate era, while marginalized voices gained representation as directors confronted uncomfortable historical truths. This revisionist approach culminated in modern iterations like "No Country for Old Men," where the American West became a landscape for examining our cultural anxieties rather than celebrating conquest.