1920s Silent Horror Movies: Pioneering Frights of Early Cinema

Silent horror films captivated audiences in the early days of cinema. These movies used visual storytelling and atmosphere to create chills without spoken dialogue. From German expressionist classics to Hollywood monster pictures, silent horror explored dark themes and pushed the boundaries of filmmaking techniques.

The 1920s saw a boom in silent horror productions. Filmmakers experimented with lighting, makeup, and special effects to bring supernatural creatures and eerie worlds to life on screen. Iconic characters like Nosferatu and the Phantom of the Opera first appeared during this era, leaving a lasting mark on the horror genre. As the decade progressed, silent horror evolved from exaggerated Gothic tales to more realistic psychological thrillers.

The Unseen Scars of Silent Cinema

Silent horror films of the 1920s reflected the deep trauma left by World War I. These movies gave voice to the unspeakable horrors experienced by soldiers and civilians alike.

The war's impact was staggering. Over 9 million soldiers died - about 6,000 each day. This loss touched nearly every family and community.

Returning soldiers often struggled with what we now call PTSD. Many sat silently, unable to rejoin normal life. Others bore visible wounds like missing limbs or disfigured faces.

For those at home, the grief was overwhelming. Young women found themselves without potential husbands, as so many young men had died. The trauma spread far beyond the battlefields.

Silent horror films captured this collective nightmare. They moved away from simple scares to deeper, more resonant fears:

- Characters wandering lost through ruined landscapes

- Human faces resembling skulls, ravaged by disease or violence

- Blurred lines between reality and imagination

- Death as an ever-present, unpredictable force

- Rats infesting every scene

- Crowds of living and dead blindly following orders

These elements spoke to audiences who had lived through the war's horrors. The movies gave form to experiences too awful for words.

Some key silent horror films of this era include:

| Film | Year | Director | Notable Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari | 1920 | Robert Wiene | Distorted sets, themes of madness |

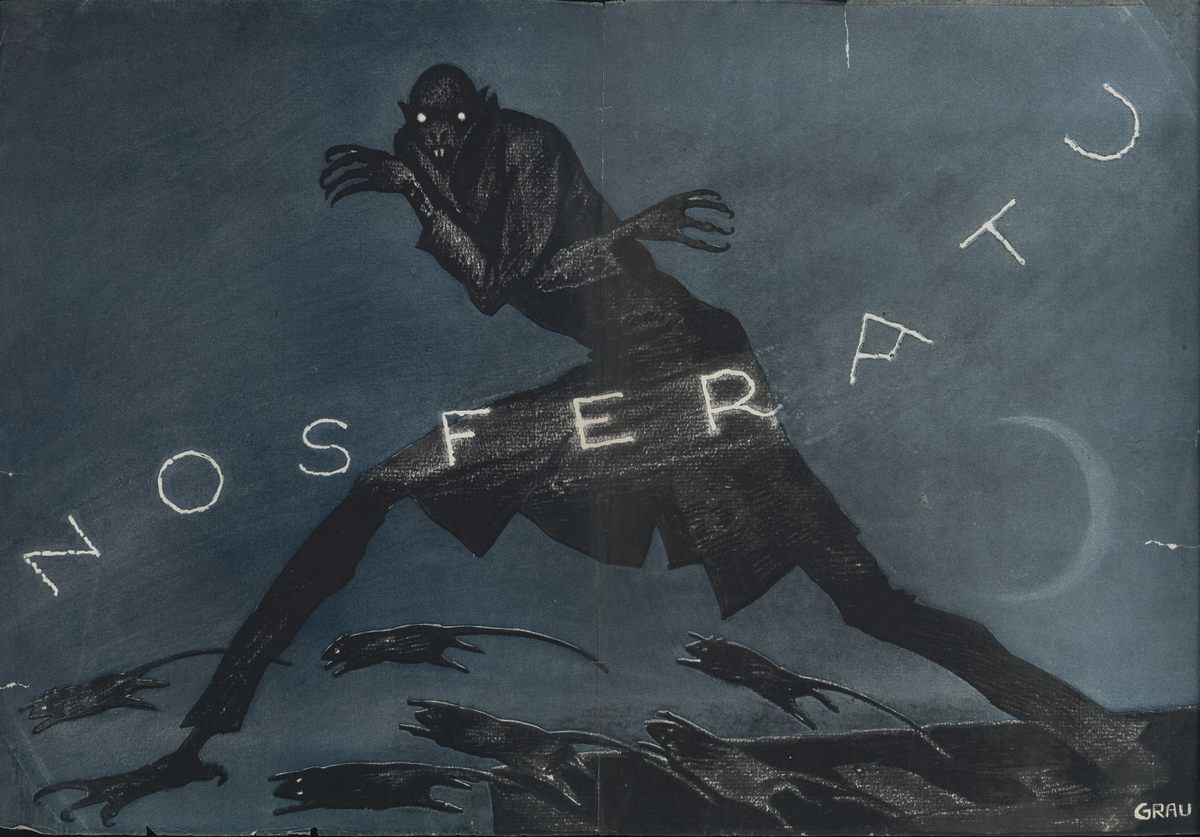

| Nosferatu | 1922 | F.W. Murnau | Plague and death spreading through a city |

| The Phantom of the Opera | 1925 | Rupert Julian | Disfigurement, masked figures |

These films still resonate today. They offer a window into the mindset of those who survived World War I. The characters on screen embody the trauma, loss, and disorientation felt by an entire generation.

The 1920s are often seen as a carefree time of wild parties. But these horror films reveal a darker truth. Many people were dancing on the edge of despair, trying to escape the shadows of war.

Silent horror became a way to process unimaginable experiences. It gave shape to fears too big for words. In doing so, it created a new visual language for terror that still influences filmmakers today.

These movies remind us of cinema's power to express the inexpressible. They stand as both art and historical document, preserving the silent screams of a shattered world.

German Expressionism in Silent Horror Films

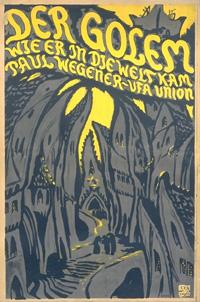

The Golem (1920)

The Golem stands as a pioneering work in silent horror cinema. Based on Jewish folklore, this film tells the story of a clay creature brought to life by a rabbi. The 1920 version is a prequel to earlier adaptations, and it's the only one that still exists today.

The movie's visual style reflects the growing influence of German Expressionism in film. Sets and costumes were designed to create an unnatural, distorted world. This approach aimed to show characters' inner thoughts and feelings through the environment around them.

Key features of The Golem include:

- Artificial-looking sets

- Exaggerated shadows

- Unusual angles and shapes

These elements work together to create an eerie, dreamlike atmosphere that became a hallmark of German Expressionist films.

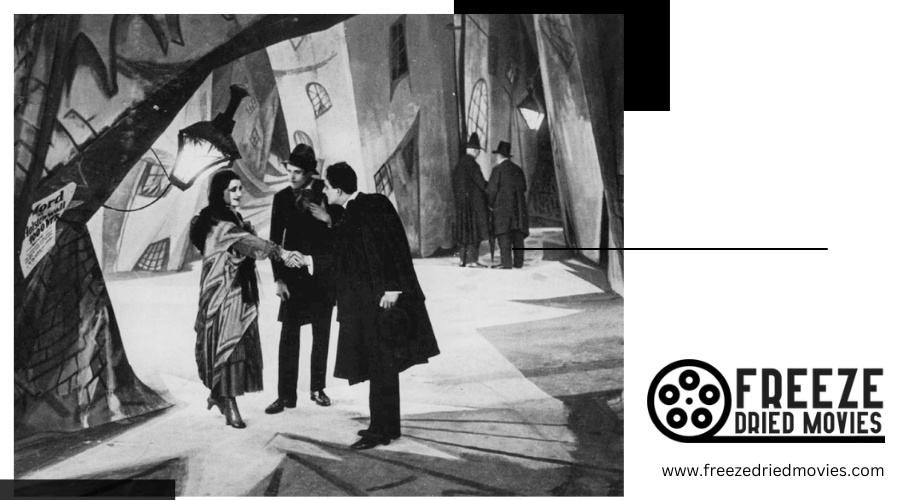

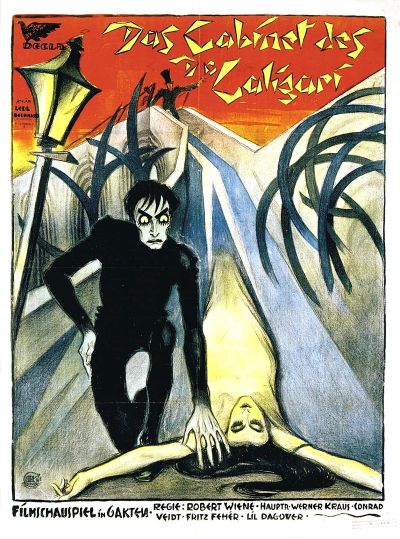

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is often called the defining film of German Expressionism in horror. Its visual style pushes the boundaries of reality, creating a world that looks like it came from a disturbed mind.

The film's set design is its most striking feature. Walls lean at odd angles, shadows are painted directly onto the sets, and shapes are warped and unnatural. This approach stems from the idea that films should be "drawings brought to life."

Some notable aspects of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari:

- Asymmetrical set designs

- Painted shadows and light

- Minimal editing between scenes

- Long takes that let viewers soak in the strange visuals

The story follows an evil doctor and his sleepwalking assistant, but uses a clever narrative structure to keep viewers guessing about what's real. This mix of visual style and storytelling creates a deeply unsettling experience.

Both The Golem and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari helped shape the look and feel of horror films for years to come. They showed how visual design could be used to create mood and atmosphere, going beyond just telling a story. These movies paved the way for future filmmakers to use visuals as a key tool in scaring and unsettling audiences.

Towards True-to-Life Cinema

From Black and White to Vivid Hues

Early horror films were not simply black and white. Many were hand-tinted to add color and mood. This process, often done by women, brought scenes to life. Night scenes shot in daylight were tinted blue to mimic moonlight. This trick fooled viewers into seeing darkness where there was none.

Filmmakers faced challenges with outdoor shoots. Indoor sets let them control light and shadow perfectly. But natural light was harder to work with. The film they used couldn't capture night scenes well. So they shot in daylight and added color later.

This method shows up in famous movies like "Nosferatu". In one scene, a vampire jumps around graves in what looks like daytime. But blue tinting made it seem like night. These touches helped create the spooky feel that horror fans loved.

The Vampire's Shadow

"Nosferatu" (1922) broke new ground in horror. F.W. Murnau mixed stylized sets with real locations. This blend added depth to the vampire tale.

The movie's villain, Count Orlok, was played by Max Schreck in creepy makeup. Orlok's castle had weird angles and shapes. But the film also showed real streets and buildings. This mix made the story feel more real and scary.

"Nosferatu" took ideas from Bram Stoker's "Dracula" book. But it changed things to avoid copyright issues. The result was a new take on vampires that still scares people today.

- Count Orlok had long fingers and pointy ears

- The movie used shadows to make scenes scarier

- Real locations made the story feel more true

Witches and Demons on Screen

"Häxan" (1922) was a strange mix of fact and fiction. Danish filmmaker Benjamin Christensen created this odd movie about witches and demons. It jumped from ancient times to the 1920s, showing how ideas about magic changed.

The film was shocking for its time. It showed:

- Graphic violence

- Nudity

- Devils and demons

Christensen framed these wild scenes as a kind of study. This clever move let him include things that might otherwise be banned. He mixed made-up stories with real history. The result was a movie unlike any other at the time.

"Häxan" had scenes of witches flying and demons being born. It also showed nuns acting crazy and women kissing a devil's bottom. These images were very bold for 1922. The movie proved that horror could push boundaries and still tell a story.

Both "Nosferatu" and "Häxan" helped shape horror movies. They showed that mixing real and fake elements could scare viewers. These films also proved that horror could tackle big ideas. They paved the way for the genre we know today.

The Face-Changing Master

Lon Chaney made a name for himself in early Hollywood by transforming into countless characters. Unlike other stars who built their careers on consistent personas, Chaney took pride in his ability to become unrecognizable from role to role. His skill with makeup and physical acting allowed him to portray a wide range of characters, often playing multiple parts in a single film.

Chaney's talent stemmed from his unique childhood. As the child of deaf parents, he learned to express emotions without words from a young age. This, combined with years of experience in vaudeville, made him perfectly suited for silent films. He excelled at playing complex villains and monsters, often with physical deformities that reflected inner struggles.

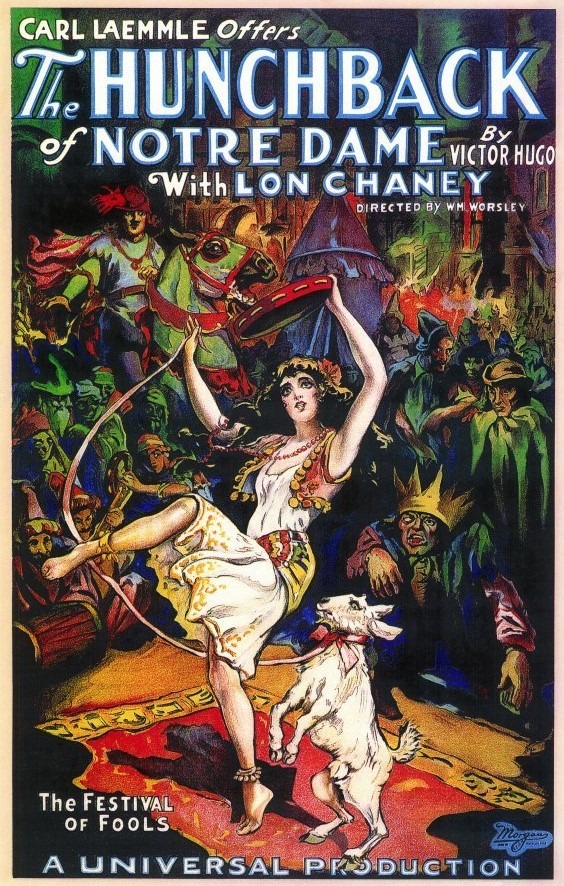

Chaney's makeup process was intense. He spent hours applying wax, greasepaint, false teeth, and hairpieces. He even used harnesses to alter his body shape for roles as amputees. While many of his films have been lost, two of his most famous works remain: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925).

The Bell-Ringer of Paris

The Hunchback of Notre Dame was a big-budget adaptation of Victor Hugo's classic novel. The film recreated 15th century Paris on the Universal backlot with detailed sets of cobblestone streets and Gothic buildings.

Chaney's portrayal of Quasimodo, the deformed bell-ringer, was key to the film's success. Like other monster characters of the time, Quasimodo's ugly exterior hid a gentle soul capable of unrequited love. This "beauty and the beast" theme became a popular story element in later films.

Chaney had wanted to play Quasimodo for years. He finally got his chance when Irving Thalberg green-lit the project. The gamble paid off - Hunchback earned over $3 million at the box office. It was Universal's most profitable silent film and showed that scary movies could be big business. This success set the stage for Universal's famous monster films of the 1930s.

The Masked Musician

After Hunchback, Chaney took on another novel adaptation. Universal bought the rights to Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera specifically for Chaney to star in. Once again, the story centered on a disfigured man causing trouble due to his feelings for a young woman. As always, Chaney designed his own makeup for the role.

Phantom wasn't quite as big a hit as Hunchback, but still earned $2 million. It was popular enough to be re-released with sound in 1930, earning another $1 million.

In both Hunchback and Phantom, Chaney created characters who looked monstrous but had deep inner lives. His performances made audiences feel for these outcasts rather than simply fear them. Chaney became the first true horror movie star, even before "horror" was a defined film genre.

Chaney often worked with director Tod Browning on dark moral tales. They made many films together from 1919 until Chaney's death in 1930. Chaney was set to star in Browning's Dracula but passed away from throat cancer at age 47 before filming began.

The Transition to Talking Pictures

The late 1920s marked a major shift in cinema. Warner Brothers' 1927 film "The Jazz Singer" introduced synchronized sound, ushering in a new era of "talkies." This technological leap changed movies forever.

Silent films had reached a high level of artistry by this time. They told stories through visual poetry, using creative camera work and expressive acting. Audiences had learned to interpret these wordless tales, finding meaning in abstract images and symbols.

The first talking pictures were less graceful. Actors had to stay close to bulky sound equipment, limiting movement. But the allure of hearing voices and sounds was strong. Moviegoers flocked to these new, more realistic films.

The change wasn't instant everywhere. Some countries, like Japan, took longer to adopt sound. A few filmmakers resisted the trend. Charlie Chaplin made "Modern Times" as a mostly silent film in 1936.

Sadly, many silent films were lost in the rush to sound. Theaters stopped showing them. Studios neglected old prints, sometimes even throwing them away. The unstable film stock used at the time easily caught fire, destroying more irreplaceable works.

Some notable silent horror films:

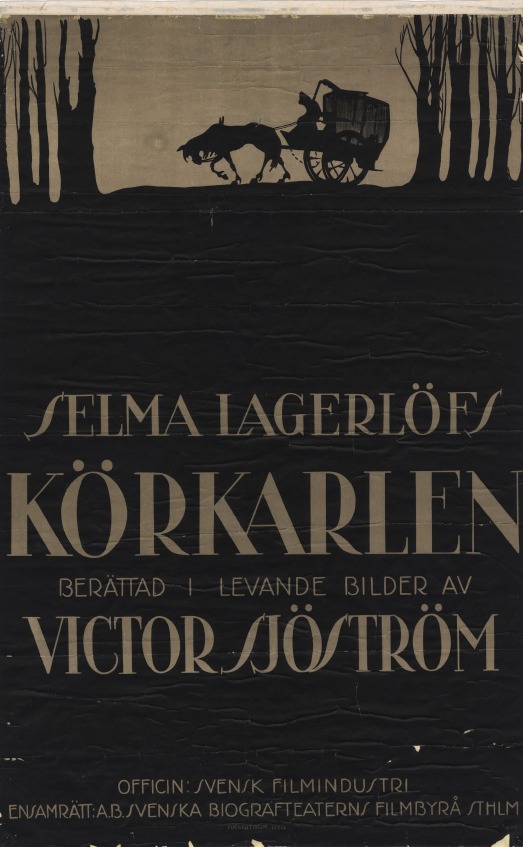

- "The Phantom Carriage" (1921): A Swedish film about death and redemption

- "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" (1920): A German expressionist masterpiece

- "Nosferatu" (1922): An unauthorized adaptation of "Dracula"

These films showcased the power of visual storytelling to create fear and unease. Without spoken words, they relied on striking imagery and atmosphere to frighten audiences.

The end of the silent era was bittersweet. While talkies opened new creative possibilities, they also closed the door on a unique art form. Silent films had developed their own language, one that spoke directly to the imagination.

Silent Horror Films in the Modern Era

Silent horror movies continue to captivate audiences in the 21st century. Film enthusiasts and preservationists have made great strides in restoring and sharing these classic works. Many early horror films can now be found in online archives, allowing new viewers to experience their eerie charm.

Festivals dedicated to silent cinema showcase newly restored prints, breathing fresh life into century-old tales of terror. These events give modern audiences a chance to step back in time and immerse themselves in the unique storytelling style of the silent era.

The visual language of silent horror films can be challenging for contemporary viewers to grasp at first. However, those who take the time to adjust often find themselves drawn into richly imaginative worlds. Early horror movies frequently used surreal imagery and dream-like sequences to unsettle their audiences.

Despite the passage of time, the emotional performances in silent horror films remain powerful. Actors convey fear, anguish, and joy through expressive faces and body language that transcend the need for spoken dialogue.

While many groundbreaking horror films from the silent era have been lost, some have survived against the odds. Nosferatu, for example, narrowly escaped destruction and lives on as a horror classic. Film preservation experts work tirelessly to track down and restore these cinematic treasures.

For those interested in exploring silent horror, here are some key films to watch:

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

- Nosferatu (1922)

- The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

- The Man Who Laughs (1928)

These early works laid the foundation for the horror genre and continue to inspire filmmakers today. Their influence can be seen in modern movies that pay homage to silent cinema techniques.